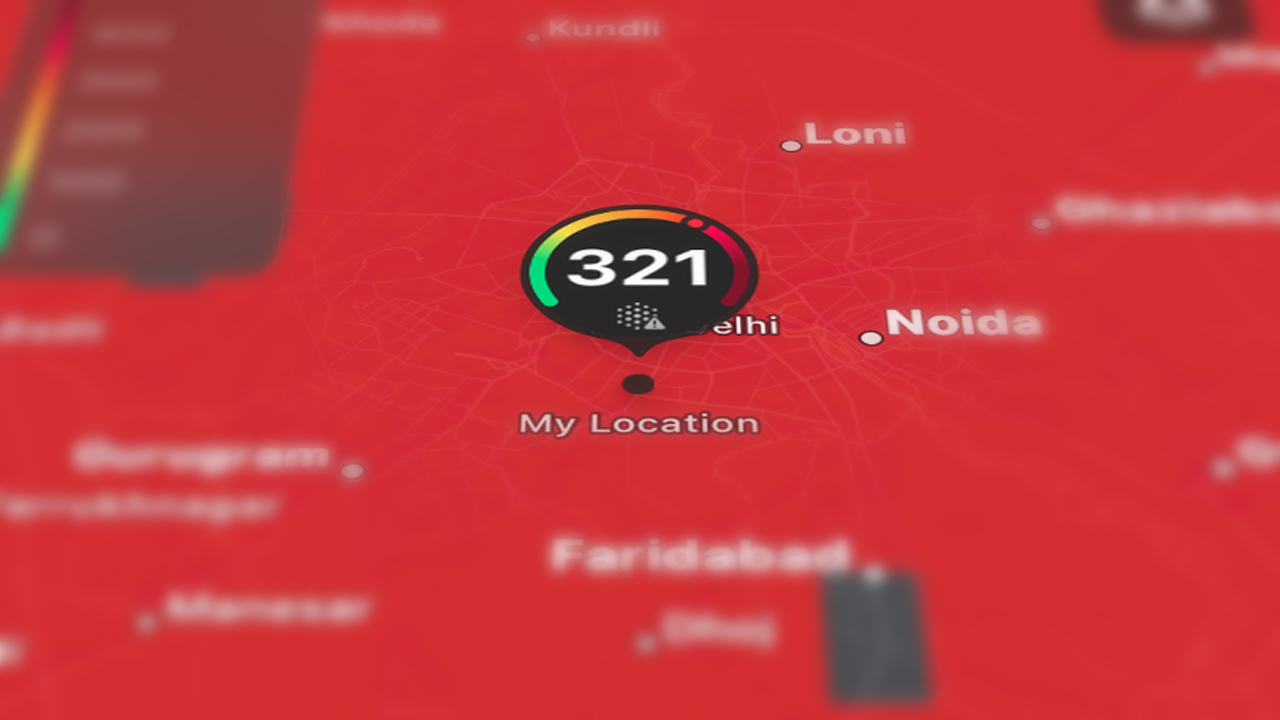

Delhi does not have a polluted air season anymore, sub-optimal air is a year-round phenomenon. According to data presented by the environment ministry in Parliament this year, Delhi could not enjoy a day of air that would be classified as good — Air Quality Index (AQI) under 50 — in the first six months of this year.

What is more telling is that the city managed only seven satisfactory and 47 moderate AQI days during this time. In contrast, the Capital was hit by 105 poor and 21 very poor AQI days (200-400). The first day of clean air was as late as September 16. And while stubble burning adds to Delhi’s woes, the city’s pollution base load is high for most months. Yet, air pollution hits the headlines only when the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) is invoked as an emergency measure. GRAP was notified in 2017 and comprises four stages, each with increasingly strict protocols to reduce emissions. It is implemented after AQI crosses the 200 threshold or just before.

But the category of 100-200 (moderately polluted) is also considered unhealthy for sensitive groups such as people with lung diseases and discomforting to people with heart disease, children and older adults. Children are particularly vulnerable as their organs are developing, and they inhale more dust playing closer to the ground. This could result in life- long compromised health. Workers who cope endlessly with dust, such as construction workers, municipal safai karamcharis, waste pickers and landfill managers, are also sensitive groups. While it is rarely headline news, 100-200 AQI is a hidden health crisis. It demonstrates the limitations of only leaning on GRAP in bad times but ignoring the air the rest of the year. Systemic changes based on cumulative data and experience are our solution.

But such evidence-based actions are missing. Closing schools is a case in point. By closing them, the State expects students will stay home, minimising their exposure to polluted air. Yet, without reasonable supervision, they tend to step out, especially if their homes are small or are in jhuggis. Chintan observed slum children playing outdoors in hazardous air during previous school closures. Their parents, informal economy workers, had to work. Why not roll out an institutional shift that cuts down summer or other breaks and creates annual air pollution breaks when the data suggests it will worsen? Why not train parents and children about protocols? Why not change the sports timings to the cleanest times, between noon to 4 pm, since AQI is likely in the 100-200 category most days? Institutionalising shifts that fight exposure while reducing AQI are likely to keep children safer than ad-hoc close-downs.

The solutions to reducing air pollution are well known: Shift the poor from biomass for cooking to clean fuels, push cleaner construction, reduce landfill fires, and increase reliable public transportation — for the most part. But each of these must be systemic, not piecemeal. They need ecosystems, not just procurement and campaigns. For example, while electric buses are a boon, advertising their routes and pushing the middle classes into them is also essential. Helping neighbourhoods understand construction norms is key to monitoring outside GRAP periods. But as a society, we can only set this in motion if we acknowledge our air is mostly unhealthy and continues to harm us relentlessly.

admin

I help fin-tech digital product teams to create amazing experiences by crafting top-level UI/UX.

Similar

admin

October 15, 2003Composting of Wet Waste

Training waste workers and households in composting to divert wet waste from landfills and abate methane emissions.

admin

April 16, 2004Waste Rules in India

Read More

admin

September 16, 2004The Poison Within – How Environmental Contamination is Impacting Our Children ’s Future

How environmental contamination is impacting our children’s future